Tackling the problem of childcare

Published: 13 Dec 2017

|  |

By Helen Norman and Colette Fagan, University of Manchester

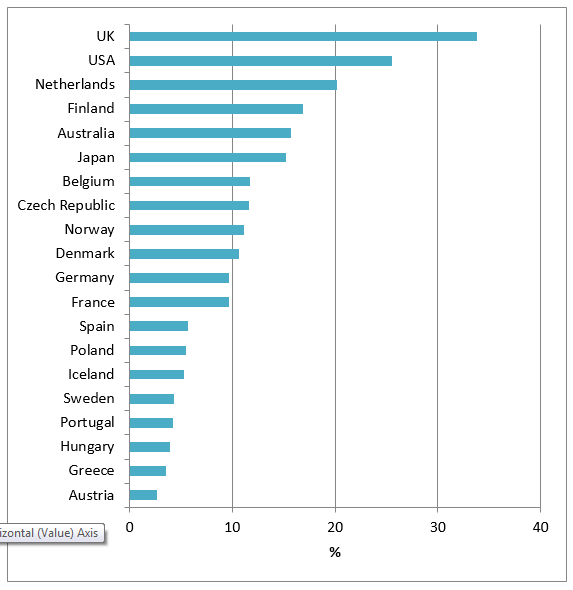

The UK has one of the highest costs for childcare in the developed world. The average household now spends £11,562 a year on their two year old’s full-time nursery fees or £15,118 a year if they live in London[1] (Harding et al. 2017). Latest figures from the Organisation for Economic and Cooperation Development (OECD) show that in the UK, the cost of full-time, pre-school childcare is now equivalent to a third of the average wage compared to less than 10% of the average wage in other countries such as Germany, France and Sweden (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Net cost of full-time pre-school childcare as a % of average earnings, 2016

Source: OECD, 2016.

What is being done about it?

In September, free early education was doubled to 30 hours a week during term-time for all three and four year old children across England. Tax-free childcare, introduced in April, allows parents in England to open an account to save for childcare costs – for every 80p that is paid in the government tops-up the account with 20p to a maximum of £2,000 per child (or £4,000 if the child is disabled). The roll out of Universal Credit means that many low income families now benefit from having 85 per cent of their childcare costs covered. Yet problems with accessibility and affordability remain.

Why are the new initiatives not working for everyone?

The 30-hours free childcare offer recently came under fire by the Organisation for Economic and Cooperation Development (OECD) because it is targeted to employed parents (who can earn up to £100,000 each) rather than helping the most deprived families. Given each parent must earn, on average, a weekly minimum equivalent to 16 hours at the National Minimum or Living Wage, those who are not employed, on zero hours contracts or very low pay will not be eligible for this support. The UK has a high proportion of children in workless families, including lone-parent families, and these families, who need it the most, will miss out (see Weale 2017).

On top of this, the funding formula for the 30-hours offer diverts resources away from state nurseries that are disproportionately attended by disadvantaged children. So although the 30-hour offer is expected to help more parents return to the workplace, it is being implemented at the expense of high-quality early years education, which particularly benefits children from poorer families. Potentially, this could widen the education gap between advantaged and disadvantaged children before they start school (Waldfogel and Stewart 2017).

There are other concerns with the implementation of the 30-hour offer:

- Only a third of local authorities are reported to have enough places to meet demand (Harding et al. 2017). Thousands of providers have closed this year because the government is under-funding the new scheme (see Ferguson 2017).

- It is not compatible with many full-time jobs. In 2016, average weekly full-time hours were recorded as 36.6.

- The provision is not available until the child is three years old so there is a childcare gap between the end of maternity leave and the start of the entitlement.

- There have been concerns that the Government’s sole focus on improving the affordability of childcare is jeopardising the quality of care. According to the Sutton Trust, a third of staff working in group-based childcare lack English and/or maths at GCSE (Waldfogel and Stewart 2017).

There are also limitations with the support provided through Universal Credit. It is not available to 60% of households because not all adults earn enough to pay tax (Hirsch and Hartfree 2013), and it can only be claimed for the first and second child. Finally, the subsidy provided through Tax-Free Childcare may just simply push up childcare prices rather than lowering the overall cost of care. Roll out of the Tax-Free scheme for older children (aged 7-12) has also been delayed until March 2018 so for this group, it will be five years since the initiative was first announced.

So where do we go from here?

Given persistent shortfalls, the following measures are needed to develop childcare provision in the UK:

1. Address the childcare gap for children aged 1 to 3. This can be achieved by:

- Providing affordable childcare from the end of maternity leave (52 weeks after the birth) to enable mothers to return to paid work. If the mother resumes employment, it has further positive implications as our research shows that fathers are more involved in looking after their pre-school children if the mother returns to full-time employment (see Fagan and Norman 2016; Norman et al. 2014; Norman 2010). If the mother is employed full-time, this also makes it more affordable for fathers to take leave or reduce their hours.

- Making it easier for fathers to adapt their work to be involved at home through well-paid parental leave, which includes a period reserved specifically for the father, and easier access to flexible working.

2. Increase funding for local authorities to provide nurseries and childcare to meet demand for the 30-hour offer with employers also playing a greater role in funding childcare for working parents.

3. Quality improvements for the childcare workforce – so that all practitioners in the childcare sector are qualified to minimum Ofsted requirements (i.e. a manager at NVQ Level 3, and at least half the staff at Level 2 in each setting).

For more information about tax free childcare see our advice pages. You can also call the Working Families helpline on 0300 012 0312 for advice and information.

References

Fagan, C., Norman, H. (2016): ‘What makes fathers involved? An exploration of the longitudinal influence of fathers’ and mothers’ employment on father’s involvement in looking after their pre-school children in the UK’ in Crespi, I., Ruspini, E. (ed): Balancing work and family in a changing society: the father’s perspective, Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke

Ferguson, D. (2017) A thousand nurseries close as free childcare scheme falters, The Guardian 18 November 2017:

Harding, C., Wheaton, B., Butler, A. (2017) Childcare Survey 2017, Family and Childcare Trust:

Hirsch D. and Hartfree Y (2013), Report: Does universal credit enable households to reach a minimum income standard?, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, p. 18. Report available at: http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/universal-credit-income-standards-full.pdf

Norman, H. (2010) Involved fatherhood: An analysis of the conditions associated with paternal involvement in childcare and housework (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Manchester

Norman, H., Elliot, M. and Fagan, C. (2014) ‘Which fathers are the most involved in taking care of their toddlers in the UK? An investigation of the predictors of paternal involvement’, Community, Work & Family, 17:2, 163-180

Norman, H. and Fagan, C. (2017) What makes fathers involved in their children’s upbringing? Working Families Work Flex Blog, 20 January 2017:

Norman, H. Watt, L. (2017) Why aren’t men doing the housework? Working Families Work Flex Blog, 29 August 2017:

OECD (2016) Society at a Glance 2016: OECD Social Indicators:

Waldfogel, J., Stewart, K. (2017): Closing Gaps Early: The role of early years policy in promoting social mobility in England, The Sutton Trust: London:

Weale, S. (2017) Tories’ 30-hour free childcare plan fails to target poor families, says expert, The Guardian 21 June 2017:

[1] Calculations by Harding et al. (2017) are based on 50 hours of childcare per week